Women's Dressways at the Turn of the Century: Ad McFadden and More

As of yet there appears to be little concise scholarship specific to the context of the fashions of clothing furnished and worn among the population of Appalachian women around the turn of the century c. 1900-1910 in Western North Carolina. In order to contextualize these pictures from the Frank Fry collection as clearly as possible it is necessary to reference both the logistical and cultural significances of clothing as something that could be purchased, produced, or modified to suit the needs of a great variety of people, but particularly of women, and particularly in this region at this time. But where to begin without a specific source discussing this topic?

Perhaps it is best to make some basic observations about the photographs themselves and the locales they occurred in. “Ad McFadden at Ledbetter” includes the presumed subject, a woman by the name of Ad McFadden. She is not someone I have been specifically able to identify a connection to the Fry family with. Ledbetter, on the other hand, presumably refers to Ledbetter Creek, Bryson City. McFadden wears a hat with her hair pulled up. Her face appears blurred, as though she has turned her head while the photo is being taken, or Frank Fry has left her out of focus, making her features indiscernible other than the fact that she has dark hair and white skin. She wears a white blouse tucked into a skirt with a black belt and a pair of boots. She stands on top of a rock in the creek that is part of a cascade formation, looking upstream with a watch on her hip. The photograph “Alma Fry Wheeler” presents the subject, Frank Fry’s sister, in what appears to be a less ornate outfit on account of the apron incorporated into it and the lack of a fine hat and other accessories present in other photographs of Alma in the collection. The ivy backdrop of this photograph is utilized again in several other photographs of other figures in the family, including Mary Rowena Pender, mother of Frank’s wife, Mattie. Alma’s hair is pulled back into a bun fastened with a white ribbon. She wears a brooch that it is difficult to determine much about in detail, other than it being fastened to her shirt and dangling a circular, smooth, medallion. She stands with her eyes shut, hands clasping the stem of a white flower.

There are a few things that we can latch onto of distinction in the photograph of Alma. The clothing is very clean and in good shape. The Fry family was well-off, being decently economically established with their business with the Entella Hotel, Frank’s role as the Superintendent of The North Carolina Talc and Mining Company, and business ventures in the lumber industry inherited from his father, a sawyer. The landscape of Appalachia at the turn of the century was transforming into a much more accessible one for trade with the extension of railways, and it is very plausible that among the Fry family that they had other opportunities to purchase clothing and accessories, as well as having likely brought clothing into the region. In short, catalogues and fashion magazines may seem anachronistic with the picture of Appalachia that is commonly portrayed, but the presence of the railroad running near to Bryson City means that there is a significant probability that clothing could be acquired. Despite the fact of this more extensive accessibility, the trends in the fashion on display do not forego all manner of traditional garments in favor of either fanciful or practical means.

Consider, for example, the apron Alma wears with her dress. This feature was commonly associated with the role of domestic servant, cook, or a lady of a household occupying one or more such positions. Beyond that, aprons did not appear in period catalogs as a form of ‘fashionable dress,’ delineated as they were and, to some extent, still are with service labor. This fact places the clothing of choice at an interesting nexus between being personal choice, accommodating necessary work, and upholding a traditional expectation for women’s dress code. Elsewhere in the world throughout the years between 1870 through at least 1914 women in other contexts were negotiating very similar considerations with their costume.

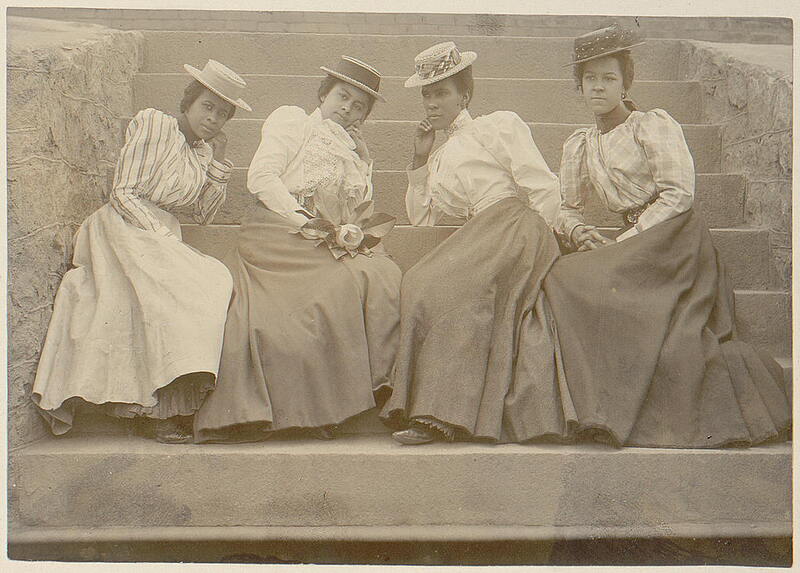

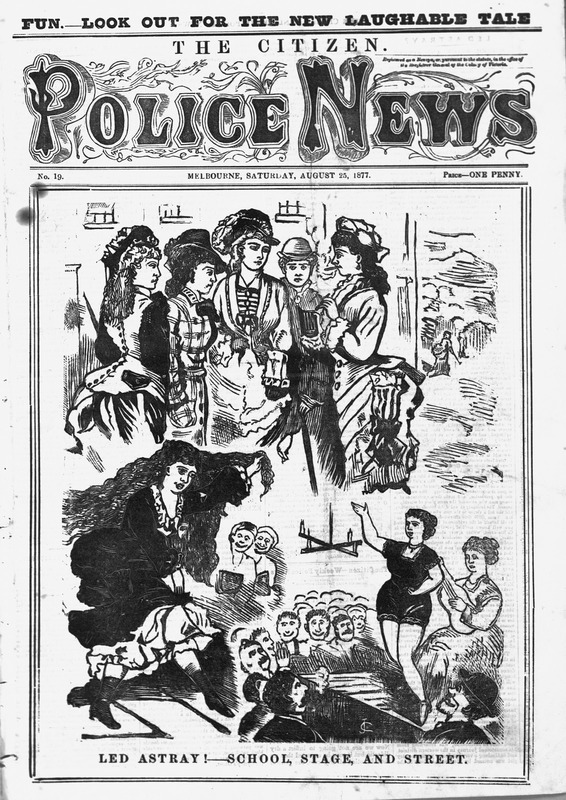

For lower class women in urban conditions this might be seen with the features of ‘flash’ fashions, which had a contemporary association with perceived moral decay and a retrospective assumption that may equate the dynamic nature of these fashions with modernity, however, the research of Bellanta and Piper illuminates that such fashions were often a more complex negotiation of nuance between traditional dress codes associated with gendered and consumptive practices alongside a relationship with turn of the century industrialization and a kind of necessity in various professions to illustrate street wisdom and sexual knowledge, but hardly an exclusive influence from either one source or another. In a similarly transitional fashion, the freed African American women of the period between 1890-1914 experienced both oppressive limitations on their labor and consumption due to the Slave Codes that would later become Jim Crow laws in the South but nevertheless expanded into middle class consumers through increased participation in service industries and consequential greater economic independence. Similar undercurrents with greater freedoms are probable influences on the choices to engage with more practical outdoor clothing in the case of McFadden, albeit combined with an outfit that largely resembles a respectable style of dress. Similarly, more conspicuous decoration in outfits worn by Alma in various photos represent a diverse wardrobe driven by work, personal taste, and expectation.

-Dylan Pope

Sources

Bellanta, Melissa and Alana Piper. "Looking Flash: Disreputable Women’s Dress and ‘Modernity’, 1870–1910." History Workshop Journal, vol. 78, 2014, p. 58-81. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/555991.

Hunt, Patricia K., and Lucy R. Sibley. “African American Women’s Dress in Georgia, 1890-1914 A Photographic Examination.” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, Jan. 1994, pp. 20–26, doi:10.1177/0887302X9401200203.

Travel Western North Carolina https://www.wcu.edu/library/digitalcollections/travelwnc/1910s/index.html