Midwifery in early 20th Century Appalachia

Throughout the Frank Fry photo collection, there are numerous photos of Mattie with one or a few of her children. Frank and Mattie lived in Hewitt, North Carolina between 1900-1914. Throughout those 14 years, Mattie delivered seven children. For her first delivery, Mattie stayed in the home of her physician in Murphy, North Carolina until her son was born. Her following six babies were delivered in Hewitt, presumably in her home. Though most of the United States had transitioned from home to hospital births by the 1920’s, southern Appalachia saw a continued reliance on midwives for delivery assistance well into the 1940s. Much of the information cited on this page comes from Shaunna Scott’s article, “Grannies, Mothers, and Babies: An Examination of Traditional Southern Appalachian Midwifery,” and examines the prevalance of "granny women," or midwifery practices in Southern Appalachia. You can view Scott's entire article here.

Childbirth was often an occasion for adult women to gather. Older children were usually sent to a neighbor's house until after the delivery, while the midwife would invite female relatives or neighbors to aid her or the mother. Sometimes midwives and neighbors would arrive a few days early - cleaning and doing chores - and stay a few days after delivery. Some midwives would include the father in the process, while others excluded him.

Reasons For Continued Use of Granny Women

Several reasons contributed to the continuance of midwifery in early 20th century Appalachia. Typical of most Southern highlanders, these midwives—often referred to as “Granny women”—were willing to help those in need, and served their neighbors and relatives living within a few miles of their homes. Doctors or physicians were scarce, and therefore often too far away from laboring women. By the time they could have called for a doctor, and waited for him to traverse the mountain and arrive at her bedside, a mother would have typically already delivered. In eastern Kentucky at this time, midwives outnumered doctors 14 to 1.

Helen C. Vance writes in The Heritage of Swain County a story of the first resident physician of Bryson City. She tells of Dr. West receiving a call to tend to a patient on the other side of the river, before the building of a bridge to cross. At one point, his horse and buggy were swept downstream and the doctor drowned. For midwives that lived amongst the women they were helping, carrying little to no equipment, it would have been much easier for them to travel to delivering mothers.

Source: Helen C Vance. The Heritage of Swain County, edited by Hazel C. Jenkins and Ora Lee Sossamon, Swain County Historical and Genealogical Society, 1988.

Another reason for continued reliance on midwives in the mountains is the financial benefits. Doctors typically charged between $10 to $30 for delivery, while midwives’ fees were typically between $3 and $5. Some patients couldn’t even afford that fee and would instead barter with midwives, or paid in food, goods, gifts, and favors instead of cash. In some cases, midwives worked for nothing in return.

Though perhaps the most convincing reason for the continued use of midwives over physicians was based on the attitudes of mountain women. Appalachian women did not have a strong trust in allopathic, modern doctors and often only referred to them as a last resort. In addition to their distrust of doctors, most mountain women did not consider pregnancy to be a condition that required medical attention, and therefore would not have been likely to call for their assistance during childbirth.

The following three excerpts from interviews cited in A Study of the Southern Appalachian Granny-Woman Related to Childbirth Prevention Measures. illustrates this point well:

Mrs. Robert Avery: It used t’be all they had nearly back in my early days. About all my

family was delivered that way.

Mrs. Andy Webb:I’d rather have a midwife any time as a doctor. They know their business, and a doctor don’t care. You got that, didya’? I ain’t no hand fer a doctor. I want ya’to know and understand it. I ain’t. He might do somethin’ t’help your back, and then he’ll reach out and get your pocketbook and that’s all he wants. When I get in pain and get t’hurtin’ or get sick, th’midwife’s th’one I go to.That’s th’only one will help anybody if they ain’t got a big pocketbook.

Mrs. Jan MacDowell: My mother was a granny woman for about all of th’community. They come after her ‘cause she was their doctor. People’d come after her, and she’d just always go. They just depended on her same as th’doctor.

In Mattie Fry's case, she delivered her first baby at the home of her physician in Murphy, NC. However, each of her subsequent deliveries were at Hewitt. It seems to be very likely that the rest of her 6 babies were delivered in her home, perhaps for the reasons listed above. With each delivery, Mattie obviously had more children in her care. One might guess that, in addition to reasons listed above, perhaps she would not want to leave her other small children at home while she made the long journey to deliver elsewhere.

Statistics Among a Group of early 20th Century Southern Appalachia Midwives

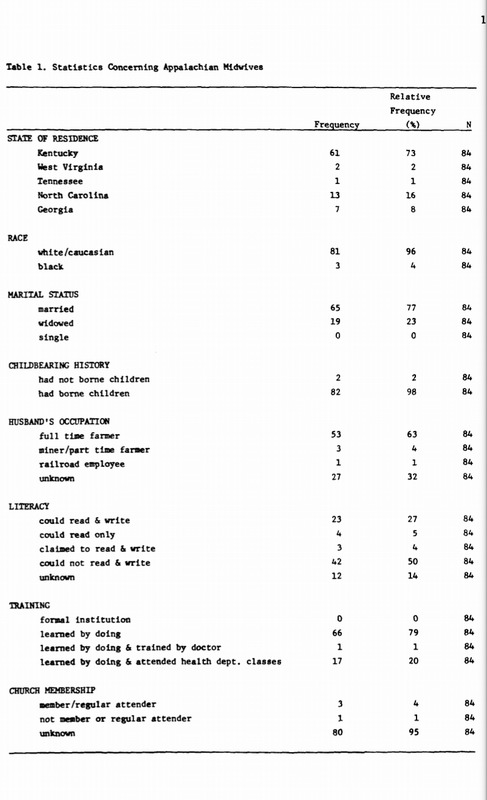

The table below demonstrates data from Shaunna Scott's article "Grannies, Mothers, and Babies: An Examination of Traditional Southern Appalachian Midwifery." Scott interviewed 84 midwives, all of whom had worked or were working in eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina and northern Georgia. These women practiced primarily during the 1920s and 1930s, though a few continued midwifery activities into the 1940s and 1950s.

As you can see in the chart, the vast majority of midwives in this sample were white, married (no single women), had borne children of their own, and were wives of farmers. Half of them could not read or write. None of them attended a formal institution, and 79% of them "learned by doing." Scott notes, "Since more black midwives practiced in the mountains of West Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia than in Kentucky, fewer blacks appear in this sample of the entire Appalachian region's midwives." Sometimes midwives worked and attended births with phsyicians. In this case, midwives often arrived before the doctor, delivered the baby, and then “handed the reins” over to the physician after the fact.

Among those interviewed for Scott's study, the range of babies delivered by each woman ranged from 7 to 760.

Source: Scott, Shaunna. “Grannies, Mothers and Babies: An Examination of Traditional Southern Appalachian Midwifery.” Central Issues in Anthropology, vol. 4, no. 2, 1982, pp. 17–30., doi:10.1525/cia.1982.4.2.17.

Traditional Folk Medicine & Procedures Amongst Appalachian Midwives

There is some controversy lasting still today in regards to Granny women, and whether or not they did more harm than good for mothers and infants. Some accounts claim that midwives' knowledge of herbs and natural medicines cured many ailments, and other accounts blame strange practices and "folktales" as causing further damage. One interesting statistic from Scott's data concludes a comparatively low number of cases of puerperal sepsis. This was likely not because of an "extreme concern for sterile delivery conditions, but perhaps because midwives, unlike doctors, did not regularly deal with the sick and, therefore, did not carry as many germs to the mother in labor."

While physicians used forceps to assist with delivery, most midwives did not carry their own equipment to births. Instead, they used whatever was available to them in the homes of the delivering mothers. Manual adjustment of the baby's position in order to ensure proper descent into the birth canal was required frequently. The use of specific teas was also very common: hot ginger tea eased labor pains, catnip tea insured a baby's first bowel movement; teas made of either chimney soot or apple tree and black gum bark stopped bleeding; pepper, rattleweed, blueberry, rasberry, bluebell, ginger and black gum bark tea were used to speed up lengthy labors; angelico or "jellico" root helped with afterbirth pains; and catnip tea cured the "hives," "cleared up the liver," and was sometimes used to feed a baby whose mother's milk was insufficient.

Source: Scott, Shaunna. “Grannies, Mothers and Babies: An Examination of Traditional Southern Appalachian Midwifery.” Central Issues in Anthropology, vol. 4, no. 2, 1982, pp. 17–30., doi:10.1525/cia.1982.4.2.17.

During pregnancy, mothers were instructed not to pass under a mare's neck, in order to prevent carrying their baby an additional two months. They were also told not to raise their arms above their heads for fear of the umbilical cord wrapping around the baby's neck.

Another method of inducing labor was known as "snuffing" or "quilling," which involved the mother sniffing pepper or snuff from a plate under her nose. This was done in hopes of inducing a sneezing attack that would trigger contractions. Before labor, a sharp object - usually an axe, knife, or pair of scissors - was placed under the mother's bed sharp-side up to "cut" the labor pains.

After delivery, the afterbirth was usually buried, disposed of in a stream of running water, or burned to prevent the mother from having childbed fever. Warm poultices made of milk and bread, onion and cornmeal, cow dung, or potato skins were used to treat mastitis. Sometimes a cloth soaked in camphor was applied to engorged breasts to draw out the milk, or, since breast pumps were unavailable, puppies, piglets, and goats were encouraged to suckle the breasts.

Some midwives thought childbed fever - a bacterial infection of the endometrium caused by unsanitary birthing procedures and conditions - could be prevented by having the mother remain in bed in her afterbirth for a few hours or several days. If the sheets were changed too early following delivery and the mother contracted childbed fever, she was sometimes treated by hanging a piece of meat fat coated in pepper around her neck and having sulfur blown into her throat.

Source: Cavender, Anthony. Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia. The University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Sources Used:

Cavender, Anthony. Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia. The University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Douthit, Jean Sandlin. "Frank Emmett and Martha Emerelda Pender Fry," http://www.friendsofthebccemetery.org/files/biographical/Fry_%20Family_History.pdf

Masters, Harriet P., "A Study of the Southern Appalachian Granny-Woman Related to Childbirth Prevention Measures." (2005). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1004. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1004

Scott, Shaunna. “Grannies, Mothers and Babies: An Examination of Traditional Southern Appalachian Midwifery.” Central Issues in Anthropology, vol. 4, no. 2, 1982, pp. 17–30., doi:10.1525/cia.1982.4.2.17.

Vance, Helen C. The Heritage of Swain County, edited by Hazel C. Jenkins and Ora Lee Sossamon, Swain County Historical and Genealogical Society, 1988.

This page was written by Meghan Harrison.